Editors note: This is part 2 in the two-part Vault "Potato-gate" series about the 1986-1987 North Dakota scandal. Find part 1 here .

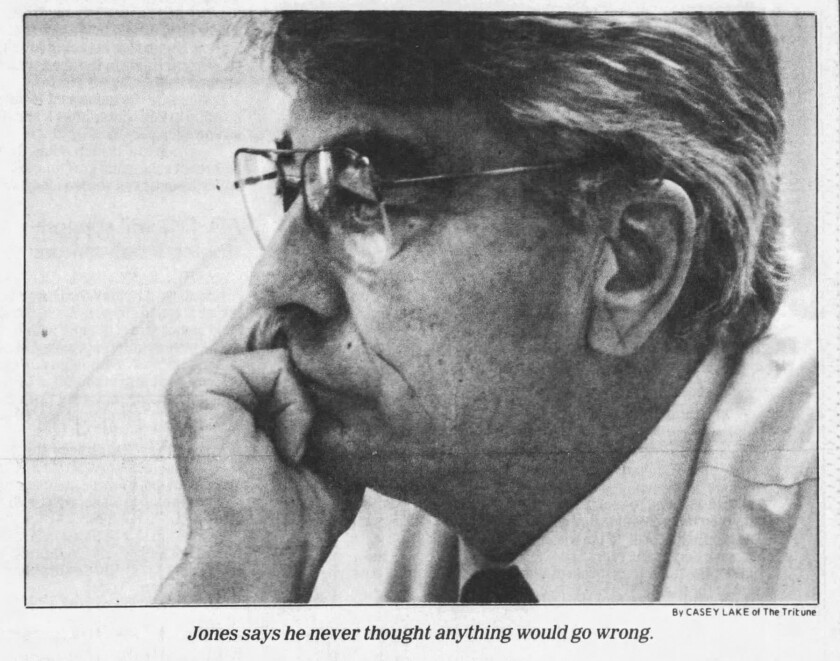

BISMARCK — Just when it seemed the North Dakota potato scandal couldn't get any worse in 1986, Kent Jones, the state's agriculture commissioner, received promising news: the Honduran farming cooperative Ahpropapa was ready to pay $106,000 for North Dakota potatoes they purchased in June of that year.

And a representative would bring the check to North Dakota in person. After more than four stressful months, farmers, like Walhalla-area Robert Dunnigan, owed $16,000, Milton “Stub” Warner of Grand Forks, LeRoy Gothberg, president of Northwest Chemical Co., East Grand Forks, Minnesota, and other truckers and chemical dealers, could finally be paid.

Not everyone at the time was convinced the promised payment was real.

“It’s not a payment until it’s a good note, as far as we’re concerned,” said Allen Hoberg, assistant attorney general assigned to work with North Dakota’s Export Trading Co. at the time.

ADVERTISEMENT

It was the latest development in what has been called "potato-gate," a scandal in North Dakota in the 1980s in which some state officials acted on a secretive scheme to sell potatos to a farming cooperative in Honduras. The scandal shook the foundations of governance, sent two people to prison, forced the Honduran Army to collect a debt and created a reputation that politicians in the Peace Garden State were a "bunch of idiots."

The information in this article was obtained from The Forum, Forum archives, North Dakota State University Archives and the Bismarck Tribune.

The entire state held its breath as potato headlines dominated the front pages for the next week, and sighed heavily when the cooperative changed its mind, saying the check was “in the mail,” according to news reports.

Multiple sources reported that the check arrived, but that it couldn't be cashed until 1987. Strangely, or rather predictably as part of Potato-gate, the check was never sent.

North Dakota Attorney General Nicholas Spaeth, who was part of the investigation into Potato-gate, then asked a federal court to force Jones and Thorndal to pay for the $300,000 bank note if the state was held liable for it in court. The state of North Dakota also filed a lawsuit in federal court saying that it should not be held liable, and American Express Bank of Miami countered, saying that if the state was not liable, then the culprits involved — Jones, former president of the Bank of North Dakota Herbert Thorndal — were.

Miami-based PetroLear Holdings Ltd.'s chief, William Messner, the middleman between North Dakota potatoes and Honduras, sued American Express Bank of Miami demanding that his accounts be unfrozen. Messner, "an entrepreneur whose many bubbles have burst prematurely," according to a Florida judge, was never successful, but he had expensive tastes. He started MetroLear in 1985 with $140,000 he won in a lawsuit and with money from an Ecuadorean businessman.

Accusations began flying back and forth, ricocheting everywhere and then landing on Jones after the truth was learned: A former trader for PetroLear, Peter Benitez, used the Honduran Army to collect the funds from the farmers to collect the North Dakota debt.

But the money was never turned over to the state, according to stories published with The Forum and the Bismarck Tribune.

ADVERTISEMENT

Jones accused Benitez of keeping most of the $106,000 instead of turning it over to the state’s Export Trading Co., but Benitez claimed he spent the money on salaries and other expenses at Jones’ direction.

Jones denied he gave Benitez such instructions, but later said Benitez pocketed $90,000.

Was Benitez acting on Jones’ authority or taking advantage of him? Spaeth asked.

“It’s a question of whom you believe. If it was done at Jones’ direction, where did Jones get the authority? On the other hand, if Kent had no role in this, then Kent was hoodwinked,” Spaeth said at the time.

The matter became part of an investigation led by the FBI.

Bribery, and political intrigue

The only criminal charges that arose from Potato-gate were bribery related.

Months passed, and the state never did see any profit from the potato shipments made to Honduras. By March 1987, the Industrial Commission gave up and spent $97,000 to help pay farmers owed money for the seed potatoes.

ADVERTISEMENT

By November 1987, prosecutors and investigators had compiled enough evidence to know that Messner was a con man, and that he lavished gifts as bribes to gain the attention of Agriculture Deparment marketing director Laurence McMerty. When discovered and charged, both Messner and McMerty pleaded innocent, at first.

Evidence that the FBI investigation uncovered showed that Messner met McMerty at Bismarck's Sheraton Hotel and gave him a $5,000 luxury cruise and nearly $4,000 in cash in return for pushing the trade transactions.

McMerty deposited $2,000 in cash, and purchased another $1,000 in travelers checks.

Messner admitted that he told travel agents at the time that: “Money was no object.” He wanted the “best there was” as McMerty “deserved it,” and “was worth it,” and had made Messner “millions of dollars richer.” After the transaction, Messner tried to delete the luxury cruise purchase from his credit card history, but failed.

Shortly before his trial was to begin, McMerty made a last-ditch effort to shift the blame, and accused Gov. George Sinner and Spaeth of playing politics with the potato deal’s investigation. He said that investigators failed to look at the agent, Benitez, who collected money the state was owed for the potatoes.

The potato deal “was not botched but rather sabotaged” by the Democrats, McMerty said shortly before his trial.

“They’ve known for over a year that the money was paid. They’ve known for over a year that that money had not made it to North Dakota, and they’ve done a very good job of making sure there was no investigation of that,” McMerty said.

Spaeth argued that there had been an investigation, but it was not discussed as he was trying to avoid embarrassment for McMerty and Jones.

ADVERTISEMENT

In court, McMerty admitted he accepted cash from Messner, but denied it was a bribe. He ended up pleading guilty to a lesser charge in September 1988, and was sentenced to 200 hours of community service at the Abused Adult Resource Center in Bismarck for what South Central District Judge Larry Hatch said was his “incredibly naive, extremely gullible” role in the Honduran potato scandal.

“My family has suffered a great deal over the past 26 months through this ordeal. It’s time to put it behind us if we can,” McMerty told Hatch after he pleaded guilty.

Deputy Attorney General Bruce Quick said at the time that McMerty’s case was “not a case with police officers and victims in the traditional sense… it is (was) a crime against the public.”

Despite his dreams of creating a successful international trading company, McMerty had been ruined financially. He quit his state job in 1987 and started his own business, but never moved away from the Bismarck area. He died in 2022 at 77 years old.

Messner played a game of cat and mouse by living in Central America for a time before Spaeth “lured Messner to New Orleans from Honduras by telling him they wanted to give him another chance to talk about the case,” according to the Bismarck Tribune.

He was arrested November 19, 1987, on a fugitive warrant issued by Spaeth, and was held in the notorious Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola until he succumbed to fighting extradition back to North Dakota.

But by January 1988, Messner, clad in light blue slacks and light blue plaid shirt, stood before Hatch to accept a plea agreement that let him off with no additional jail time, provided he repay the state for the cost of the single potato shipment: $60,888.

Messner handed over a cashier’s check for $10,000, paid the same amount in July the following year, but then asked for more time in January 1989 because he was indigent, and dying of cancer.

ADVERTISEMENT

Strangely, in 1986, Messner was diagnosed with intestinal cancer, the same year of the aborted potato deal, but he declined treatment.

“Had he sought treatment at that time it probably could have been treated,” Quick said. “So I don’t know if he had a death wish or what.”

The cancer later spread to Messner’s lungs and brain. In his final days, he convinced a doctor to allow him to smoke four to five cigarettes a day.

The “high-rolling agent,” the “flamboyant dealmaker,” the con man who hoodwinked the state of North Dakota, died Sept. 11, 1989. He was 44 years old.

“It’s a bizarre ending to a bizarre case,” Quick said after Messner's death.

Kent Jones

In a flurry of activity relating to the "infamous Honduran potato deal," Jones suffered a debilitating stroke that left him speechless and paralyzed on his right side the day after he lost his bid for reelection in 1988. He became poor, and was living off of $389.72 per month, but he kept fighting.

“Kent Jones blames bank for his stroke,” a headline in the Bismarck Tribune read on Dec. 2, 1988. He filed a $127 million dollar lawsuit against American Express Bank International of Miami charging the company’s behavior led to his stroke.

ADVERTISEMENT

American Express countersued under federal racketeering laws in U.S. District Court alleging that Jones, Thorndal and McMerty conspired to defraud the bank of $300,000.

“Their actions were intentional, fraudulent, malicious, oppressive, or taken with such reckless disregard of the risk of substantial harm to (AmEx) that (the four) are liable for punitive damages,” the American Express lawsuit stated.

Later, Jones and his wife Kathleen filed for bankruptcy.

“He lingered on for years in a nursing home. I never saw him again,” Sarah Vogel, who said she respected Jones for his empathy in dealing with issues during the Farm Crisis, recently told Forum News Service.

Jones, also a farmer as well as a politician, father of four children, died in 1995. He was 69 years old.

Herbert Thorndal

“Grumpy. He was grumpy and hmm…” said Vogel, recollecting on what kind of a person Thorndal was. “I wasn’t all that impressed with him. But I had been suing the bank too to stop them from foreclosures and I was winning. They weren’t following state law,” for banks to go through mediation before foreclosing on a farm, she said. It was a scene she described in detail in her book, “The Farmer’s Daughter.” Vogel was also featured in an article by Life magazine in 1982 for her work helping financially troubled farmers during the 1980s.

A decorated U.S. Air Force intelligence officer during the Korean War, Thorndal worked in banking jobs all his life. Upon leaving his position as president of the Bank of North Dakota on the eve of Potato-gate, he traveled to Russia as a consultant for the Agricultural Cooperative Development International, according to his obituary. He died in 2002 at 73 years old.

Nicholas Spaeth

Spaeth, the 27th attorney general of North Dakota, was “a gentleman as well as a gentle man,” and was first elected as attorney general in 1984, continuing until he “was retired by the voters,” according to his obituary.

After leaving politics, Spaeth worked as a partner in several national law firms, and as general counsel for three Fortune 250 companies. Before his death, he partnered with equity investors to create a start-up company in North Dakota's Bakken oil field.

Spaeth died in his Fargo home in 2014. He was 64 years old.